Review of thickness-shear mode quartz resonator sensors for temperature and pressure. The Torsional Tuning Fork as a Temperature. Controlling the quality factor of a tuning-fork resonance between 9 and 300 K for scaning-probe microscopy.

Quartz tuning fork for viscometers for helium liquids. Force-gradient-induced mechanical dissipation of quartz tuning fork force sensors used in atomic force microscopy. Ĭastellanos-Gomez, A., Agrait, N., Rubio-Bollinger, G., 2011. Sensors based on piezoelectric resonators. Microengineered silicon double-ended tuning fork resonators. The idealized field distribution (e,j) is much closer to the actual field distribution (c,h) for the needle sensor than for the qPlus sensor. The qPlus sensor uses a bending mode, thus the mechanical stress is maximal where the charge-collecting electrodes are located (d), while the length-extensional resonator develops a uniform stress profile (i). Parts (e) and (j) show the idealized field distribution within the quartz crystals. Parts (a), (b), (f), and (g) illustrate the geometrical dimensions as listed in Table 1 parts (c) and (h) show a schematic view of the electrostatic field in the cross sections and parts (d) and (i) show the mechanical stress profile along a cross section. A needle sensor (f) is built by attaching a light tip to one prong of the length-extensional resonator. The prong without displayed electrodes is fixed to a massive substrate (not shown here see Fig. 2b).

#Quartz tuning fork sensor free#

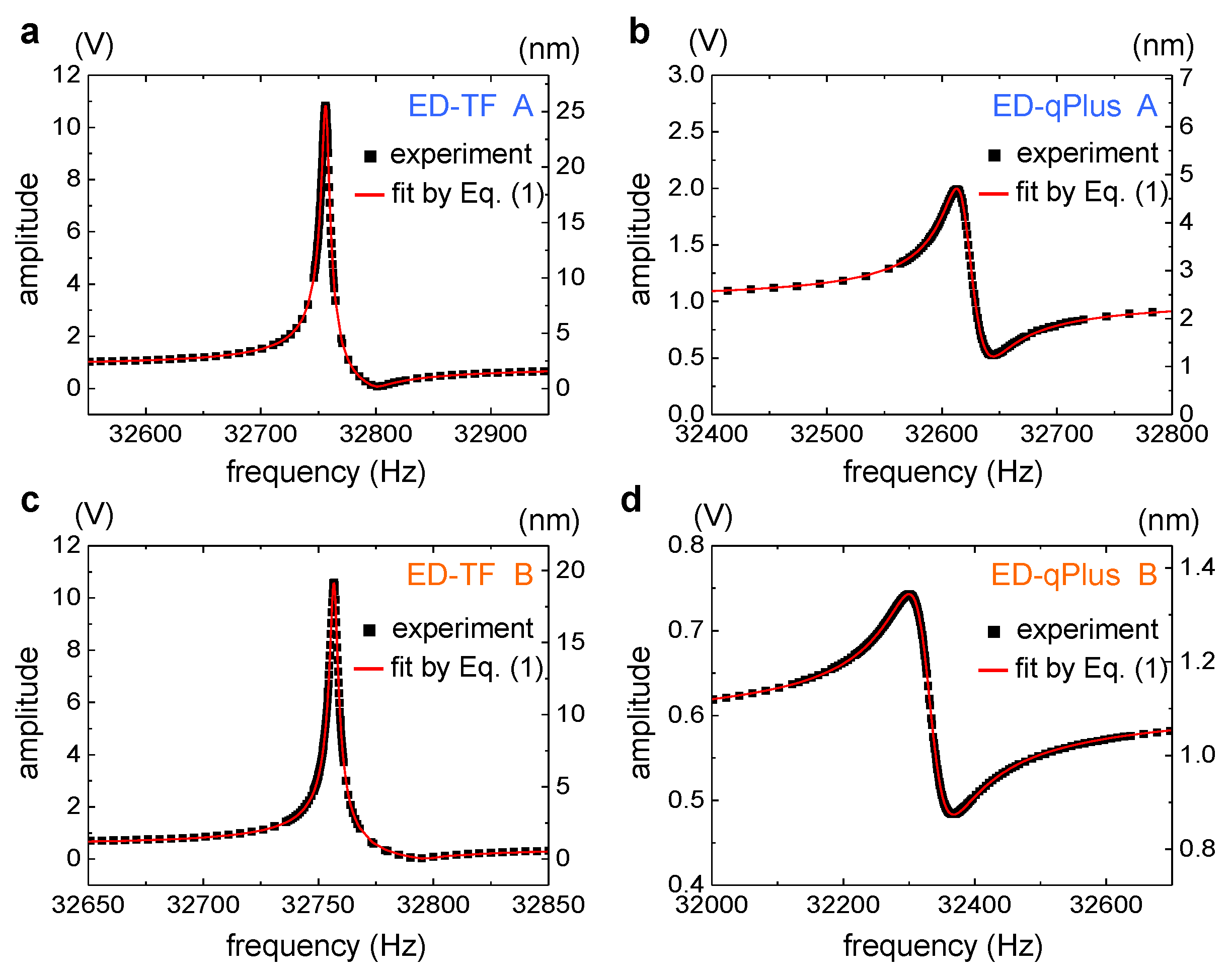

For clarity, only the electrodes on the free prong are shown. A qPlus sensor (a) is created by attaching one of the prongs of the tuning fork to a substrate and attaching a tip to the other prong. Finally, we suggest how the signal-to-noise ratio of the sensors can be improved further, we briefly discuss the challenges of mounting tips, and we compare the noise performance of self-sensing quartz sensors and optically detected Si cantilevers.įigure 3Geometry of sensors based on quartz tuning forks (a)–(e) and length-extensional resonators (f)–(j). Thus, we show that the earlier finding that quoted an optimal signal-to-noise ratio for oscillation amplitudes similar to the range of the forces is still correct when considering all four frequency noise contributions. The first three noise sources are inversely proportional to amplitude while thermal drift noise is independent of the amplitude. Thermal drift noise, however, is inversely proportional to bandwidth. Deflection detector noise increases with bandwidth to the power of 1.5, while thermal noise and oscillator noise are proportional to the square root of the bandwidth. We find that for self-sensing quartz sensors, the deflection detector noise is independent of sensor stiffness, while the remaining three noise sources increase strongly with sensor stiffness. We calculate the effect of these noise sources as a factor of sensor stiffness, bandwidth, and oscillation amplitude. We find four noise sources: deflection detector noise, thermal noise, oscillator noise, and thermal drift noise. Here, we calculate and measure the noise characteristics of these sensors. Two fundamentally different types of quartz sensors have achieved atomic resolution: the “needle sensor,” which is based on a length-extensional resonator, and the “qPlus sensor,” which is based on a tuning fork.

#Quartz tuning fork sensor upgrade#

These self-sensing force sensors allow a relatively easy upgrade of a scanning tunneling microscope to a combined scanning tunneling/atomic force microscope. Nowadays, most atomic force microscopes use micromachined force sensors made from silicon, but piezoelectric quartz sensors are being applied at an increasing rate, mainly in vacuum.

The force sensor is key to the performance of atomic force microscopy (AFM).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)